Let’s make no mistake, Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy probably left the biggest impact on the western genre at any time and from any place. The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly is consistently heralded as the greatest western ever made, garnering the #4 spot on the IMDb top 250 and a consistent citation from filmmakers as one of the most influential films ever. If you want to look at influence by sheer imitation, though, Sergio Corbucci’s Django might just sneak in to the top. Coming before The Ugly in 1965, it left quite a mark with its stoic anti-hero with a coffin he drags behind him as penance. Franco Nero made a huge mark on the genre as the lead, and he alone would star in fifteen different westerns, including the belated sequel (where Django becomes a monk, no less!) Django Strikes Again, and the similar, and fantastic, one-man-against-the-world Keoma by Enzo G. Castellari. It seemed for a time, though, that every western to follow in Django’s wake would erroneously be retitled to something in the Django name, despite the fact that few of the films even had a character named Django. Still, every Italian production for the last twenty decades, and Blue Underground clocks 50 “unofficial” sequels, all did their part in trying to replicate the style of Corbucci’s trendsetter.

It’s been thirty-five years now, though, since the gatling gun toting gunslinger first rolled into town. Is he still a good shot, or has the shine of his pistol tarnished a bit in light of all the imitations to follow in its wake. At the time of its release, it was known as one of the most violent films ever made, most famously for featuring an ear-severing scene that Tarantino would later homage in Reservoir Dogs. Still, will this be respected today as one that cultivated the genre, or does it still pack enough punch to entertain today? Saddle up, friends, let’s find some bounty.

It’s been thirty-five years now, though, since the gatling gun toting gunslinger first rolled into town. Is he still a good shot, or has the shine of his pistol tarnished a bit in light of all the imitations to follow in its wake. At the time of its release, it was known as one of the most violent films ever made, most famously for featuring an ear-severing scene that Tarantino would later homage in Reservoir Dogs. Still, will this be respected today as one that cultivated the genre, or does it still pack enough punch to entertain today? Saddle up, friends, let’s find some bounty. The film begins with Luis Bacalov’s theme that memorably bellows “Djangooooooo, have you always been alone? “ as the drifter walks through a muddied desert dragging behind him a coffin that’s too heavy to be empty. As he reaches the crest of a hill, he witnesses a woman being tied to and beaten on a bridge by Mexican bandits. Rather than rush to her rescue like any other white hatted western hero would in films prior to Django, he instead watches in silence. The guy’s got a lot more baggage than just that coffin. Looking instead to come to her rescue are a few white horsemen. Instead, they kill the Mexicans and look to punish whom Django later learns to be runaway prostitute Maria (Loredana Nusciak). In the beat of a second, though, Django unleashes a flurry of fire, shooting down the handful of bandits. He takes Maria and heads back to the brothel she ran from.

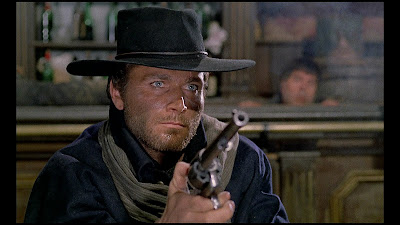

The film begins with Luis Bacalov’s theme that memorably bellows “Djangooooooo, have you always been alone? “ as the drifter walks through a muddied desert dragging behind him a coffin that’s too heavy to be empty. As he reaches the crest of a hill, he witnesses a woman being tied to and beaten on a bridge by Mexican bandits. Rather than rush to her rescue like any other white hatted western hero would in films prior to Django, he instead watches in silence. The guy’s got a lot more baggage than just that coffin. Looking instead to come to her rescue are a few white horsemen. Instead, they kill the Mexicans and look to punish whom Django later learns to be runaway prostitute Maria (Loredana Nusciak). In the beat of a second, though, Django unleashes a flurry of fire, shooting down the handful of bandits. He takes Maria and heads back to the brothel she ran from. When he enters the brothel he can’t even be taken seriously enough to get a drink. The town has been dominated by bandits demanding profits for their protection, led by Major Jackson (Eduardo Fajardo). Jackson and his boys have this little game where they unchain Mexican captives and gun them down as they try to escape. They’re badass. Django quickly commands respect, though, when he shoots down another smattering of the Major’s men in front of all the whores and their pudgy manager. He gets a drink and his pick of any woman in the joint, but Django can’t be bothered with such excess. When asked by the owner what’s inside the coffin, he responds with perfect deprecating glory, “Django.”

When he enters the brothel he can’t even be taken seriously enough to get a drink. The town has been dominated by bandits demanding profits for their protection, led by Major Jackson (Eduardo Fajardo). Jackson and his boys have this little game where they unchain Mexican captives and gun them down as they try to escape. They’re badass. Django quickly commands respect, though, when he shoots down another smattering of the Major’s men in front of all the whores and their pudgy manager. He gets a drink and his pick of any woman in the joint, but Django can’t be bothered with such excess. When asked by the owner what’s inside the coffin, he responds with perfect deprecating glory, “Django.” The Major’s men come back for Django, this time nearly fifty-strong, but in one fell swoop sends them all into the dirt with the gatling gun he’d been concealing in his coffin. He wasn’t lying when he said he himself was in the coffin, either, since he’s been punishing himself ever since he allowed his lover to be killed by the Major while he was away. Django’s back, though, and he’ll get his man, as well as maybe a little bit of gold from that paunchy Mexican general, Hugo Rodriguez (Jose Bodalo).

The Major’s men come back for Django, this time nearly fifty-strong, but in one fell swoop sends them all into the dirt with the gatling gun he’d been concealing in his coffin. He wasn’t lying when he said he himself was in the coffin, either, since he’s been punishing himself ever since he allowed his lover to be killed by the Major while he was away. Django’s back, though, and he’ll get his man, as well as maybe a little bit of gold from that paunchy Mexican general, Hugo Rodriguez (Jose Bodalo). Leone’s films found their appeal by lingering stylishly on empty, quiet moments in cinemascope, using close-ups, sound effects and Morricone’s rollicking music to inflate what was initially just another riff on Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. His great non-performance aside, Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name was essentially a cipher, an empty vessel for Leone’s skills at visual storytelling. Django as a character, though, is front and center what makes Sergio Corbucci’s film still just as compelling today. The narrative plays deliriously with our expectations, constantly flipping from presenting Django as a respectable hero and a callous outlaw. At the start we see him watch a woman beaten only to, much later, save her. He brings her to a brothel to get some sleep – a nice gesture, right? Well, apparently he was doing it at the request of the Mexican general. Okay, well she’s safe, right? Instead of leaving with dignity, he instead strikes a deal to steal a sack full of gold. Not only that, but he steals the gold a second time from his partner as he tries to make a getaway. Near the end of the film Maria finally offers herself to Django, and he looks to want to reciprocate but doesn’t. You think to yourself, “Oh, it’s the pain of losing his lover that’s holding him back”, right? Well, the next scene he declares that he doesn’t want her and instead wants the native prostitute. Dirty move, isn’t it? Well, just wait. He doesn’t pick the native for sex, but instead as a decoy so he can make off with the gold without anyone knowing. Even during the film’s memorable finale, Django is thrown once again in conflict with his valour and his villainy, forced to choose between his gold and his girl, and even then Corbucci doesn’t succumb to cliché.

Leone’s films found their appeal by lingering stylishly on empty, quiet moments in cinemascope, using close-ups, sound effects and Morricone’s rollicking music to inflate what was initially just another riff on Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. His great non-performance aside, Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name was essentially a cipher, an empty vessel for Leone’s skills at visual storytelling. Django as a character, though, is front and center what makes Sergio Corbucci’s film still just as compelling today. The narrative plays deliriously with our expectations, constantly flipping from presenting Django as a respectable hero and a callous outlaw. At the start we see him watch a woman beaten only to, much later, save her. He brings her to a brothel to get some sleep – a nice gesture, right? Well, apparently he was doing it at the request of the Mexican general. Okay, well she’s safe, right? Instead of leaving with dignity, he instead strikes a deal to steal a sack full of gold. Not only that, but he steals the gold a second time from his partner as he tries to make a getaway. Near the end of the film Maria finally offers herself to Django, and he looks to want to reciprocate but doesn’t. You think to yourself, “Oh, it’s the pain of losing his lover that’s holding him back”, right? Well, the next scene he declares that he doesn’t want her and instead wants the native prostitute. Dirty move, isn’t it? Well, just wait. He doesn’t pick the native for sex, but instead as a decoy so he can make off with the gold without anyone knowing. Even during the film’s memorable finale, Django is thrown once again in conflict with his valour and his villainy, forced to choose between his gold and his girl, and even then Corbucci doesn’t succumb to cliché. The film is constantly pulling Django’s morals from side to side, never quite allowing the audience a chance to see who he really is behind that concealing black-rimmed hat. Even that iconic coffin is one filled with duality. First we recognize it as a sort of cross he drags for penance for allowing his lover to die, but then we find out instead that it’s used to conceal his punishing weapon. With the script written by Sergio Corbucci and his brother Bruno, though, it’s never black and white. It’s always a bit of both, and the way they play with our expectations of what a western hero should be and what a western hero really was in the duplicitous Old West makes Django always compelling at every turn. There’d be a ton of films that would emulate the stoic lead pioneered by Eastwood and Nero, but few would explore the infinitely more interesting blur between hero and villain, a trait that still gives Django an edge over its imitators all these years later.

The film is constantly pulling Django’s morals from side to side, never quite allowing the audience a chance to see who he really is behind that concealing black-rimmed hat. Even that iconic coffin is one filled with duality. First we recognize it as a sort of cross he drags for penance for allowing his lover to die, but then we find out instead that it’s used to conceal his punishing weapon. With the script written by Sergio Corbucci and his brother Bruno, though, it’s never black and white. It’s always a bit of both, and the way they play with our expectations of what a western hero should be and what a western hero really was in the duplicitous Old West makes Django always compelling at every turn. There’d be a ton of films that would emulate the stoic lead pioneered by Eastwood and Nero, but few would explore the infinitely more interesting blur between hero and villain, a trait that still gives Django an edge over its imitators all these years later. Although Django doesn’t seem all that violent today, even when he’s gunning down forty men in the span of seconds, it still possess scenes of maliciousness that give its guns pop. The ear-cutting scene has been done several times since, and with greater graphic violence, but Corbucci’s film still resonates not for the violence, but for the way it’s willing to revel in the lowly behavior of its baddies. They don’t just cut off his ear, they FEED IT back to the victim. That’s how depraved this movie is. Or again, the start, where Django just quietly watches Maria tied and whipped. There are other scenes with this kind of unflinching honesty at the dissoluteness of these characters, like when the camera lingers on Django getting pummeled in the face by the butt of a rifle or when, after being bludgeoned, Django has his hands trotted over by all of the Major’s horses. It’s not so much that it’s graphic, it’s just the wanton principle behind it all.

Although Django doesn’t seem all that violent today, even when he’s gunning down forty men in the span of seconds, it still possess scenes of maliciousness that give its guns pop. The ear-cutting scene has been done several times since, and with greater graphic violence, but Corbucci’s film still resonates not for the violence, but for the way it’s willing to revel in the lowly behavior of its baddies. They don’t just cut off his ear, they FEED IT back to the victim. That’s how depraved this movie is. Or again, the start, where Django just quietly watches Maria tied and whipped. There are other scenes with this kind of unflinching honesty at the dissoluteness of these characters, like when the camera lingers on Django getting pummeled in the face by the butt of a rifle or when, after being bludgeoned, Django has his hands trotted over by all of the Major’s horses. It’s not so much that it’s graphic, it’s just the wanton principle behind it all. The sudden outbursts of malicious violence, and Corbucci’s refusal to define Django as any kind of hero proper, allow his film to constantly buck expectation and to still stand out today as one of the premier films of the genre. While personal favorites like Keoma or Mannaja may offer a grander, more poetic brutality and style, they can’t match the sheer audacity of Corbucci’s sotic little piece. Like his protagonist, Django rolls forward with little expectation but shoots through the roof with every scene following. It’s a shame that Nero and Corbucci never worked together on creating a series proper for our beloved Django. Yes, they made a couple westerns together, The Mercenary and Companeros, which are quite good, but never would they revisit the character that come to define both their careers. Leone and Eastwood got a trilogy with their Man With No Name, but for the man whose name we’ll never forget, only one. It’s a shame, but maybe it’s fitting, for there’ll never be another like Django. And as fans, we’ll continue to bellow his name as he drags the weight of all inferior westerns through the mud in his coffin. “Oh Django! After the showers, the sun…you will be shining!”

The sudden outbursts of malicious violence, and Corbucci’s refusal to define Django as any kind of hero proper, allow his film to constantly buck expectation and to still stand out today as one of the premier films of the genre. While personal favorites like Keoma or Mannaja may offer a grander, more poetic brutality and style, they can’t match the sheer audacity of Corbucci’s sotic little piece. Like his protagonist, Django rolls forward with little expectation but shoots through the roof with every scene following. It’s a shame that Nero and Corbucci never worked together on creating a series proper for our beloved Django. Yes, they made a couple westerns together, The Mercenary and Companeros, which are quite good, but never would they revisit the character that come to define both their careers. Leone and Eastwood got a trilogy with their Man With No Name, but for the man whose name we’ll never forget, only one. It’s a shame, but maybe it’s fitting, for there’ll never be another like Django. And as fans, we’ll continue to bellow his name as he drags the weight of all inferior westerns through the mud in his coffin. “Oh Django! After the showers, the sun…you will be shining!”presentation...

One thing is clear – Blue Underground’s Blu-rays always look tack sharp. The problem with a lot of them, though, is that they reach that point through some creative digital sharpening and a whole lot of noise. Django is such a disc, with amazing sharpness and detail in objects, from the individual hairs on Nero’s beard to the fine little pieces of glimmering gold in the bandits’ bag. Yet, behind all that detail is a consistent flurry of fine black dots, proving that Blue Underground really is pushing these negatives the furthest they can go in the pursuit of detail. While this is par for the course with many Blue titles, Django may suffer most given the depreciating condition of the original film elements. There are many scenes where the white flickering dissolve from the print would be glaringly obvious if it weren’t for all the black noise. Still, they’ve polished a turd of a print as nicely as they can, and Blue Underground needs to be commended for digitally removing a number of major glaring print defects on this new release. This is a major step ahead of the older DVD, which while noisy is impeccably clean and never aflutter in the gate. Colors are trademark Blue Underground vivacious and anyone remembering the film as a battered home video staple are about to see it in a whole new light.

One thing is clear – Blue Underground’s Blu-rays always look tack sharp. The problem with a lot of them, though, is that they reach that point through some creative digital sharpening and a whole lot of noise. Django is such a disc, with amazing sharpness and detail in objects, from the individual hairs on Nero’s beard to the fine little pieces of glimmering gold in the bandits’ bag. Yet, behind all that detail is a consistent flurry of fine black dots, proving that Blue Underground really is pushing these negatives the furthest they can go in the pursuit of detail. While this is par for the course with many Blue titles, Django may suffer most given the depreciating condition of the original film elements. There are many scenes where the white flickering dissolve from the print would be glaringly obvious if it weren’t for all the black noise. Still, they’ve polished a turd of a print as nicely as they can, and Blue Underground needs to be commended for digitally removing a number of major glaring print defects on this new release. This is a major step ahead of the older DVD, which while noisy is impeccably clean and never aflutter in the gate. Colors are trademark Blue Underground vivacious and anyone remembering the film as a battered home video staple are about to see it in a whole new light. Sound-wise, we get two tracks in DTS-HD Master Audio, but both are unfortunately mono only. Usually Blue Underground pulls out all the stops in their surround sound remixes, especially in their recent Blu-ray for Fulci’s City of the Living Dead, but here the best we get is one fairly deep channel. Bigger than a remix, though, is the inclusion of the Italian track to go along with the Enlgish, for it features Franco Nero’s original voice. The English dubbing certainly isn’t the best, always out of sync with mouths and, especially in Django’s case, robotically stilted. Hearing Nero in his original tongue is definitely how this should be heard, and like with the video, Blue Underground has done a nice job cleaning this up so any playback damage, like hiss, pops or dropouts, are almost entirely removed.

Sound-wise, we get two tracks in DTS-HD Master Audio, but both are unfortunately mono only. Usually Blue Underground pulls out all the stops in their surround sound remixes, especially in their recent Blu-ray for Fulci’s City of the Living Dead, but here the best we get is one fairly deep channel. Bigger than a remix, though, is the inclusion of the Italian track to go along with the Enlgish, for it features Franco Nero’s original voice. The English dubbing certainly isn’t the best, always out of sync with mouths and, especially in Django’s case, robotically stilted. Hearing Nero in his original tongue is definitely how this should be heard, and like with the video, Blue Underground has done a nice job cleaning this up so any playback damage, like hiss, pops or dropouts, are almost entirely removed.extras...

While not the full out special edition a movie of this caliber and influence deserves, Blue Underground has ported over extras from their original 2-disc release from 2008 along with a vintage documentary that was previously released on Blue Underground’s Run, Man, Run DVD. “Western, Italian Style” is a 38-minute documentary from 1968, and it amusingly plays out in that kitschy, instructional video kind of fashion. It certainly doesn’t cover the genre with breadth, but it does feature a few of the classics, namely Once Upon a Time in the West, Corbucci’s The Great Silence and Run, Man, Run. It also features interviews and on-set footage with directors Enzo Castellari, Sergio Corbucci, Sergio Sollima and Mario Caiano. Castellari’s earlier bit is the best, where he deals with a some on-screen fight choreography in amusing fashion. Forget the genre it is chronicling, though, the documentary itself is a vintage artifact more than worth preserving, and it’s great that Blue Underground included it here. It would be great to see more of this sort of thing on future releases rather than spending the money on newer, narrowly-focused interviews and commentary.

While not the full out special edition a movie of this caliber and influence deserves, Blue Underground has ported over extras from their original 2-disc release from 2008 along with a vintage documentary that was previously released on Blue Underground’s Run, Man, Run DVD. “Western, Italian Style” is a 38-minute documentary from 1968, and it amusingly plays out in that kitschy, instructional video kind of fashion. It certainly doesn’t cover the genre with breadth, but it does feature a few of the classics, namely Once Upon a Time in the West, Corbucci’s The Great Silence and Run, Man, Run. It also features interviews and on-set footage with directors Enzo Castellari, Sergio Corbucci, Sergio Sollima and Mario Caiano. Castellari’s earlier bit is the best, where he deals with a some on-screen fight choreography in amusing fashion. Forget the genre it is chronicling, though, the documentary itself is a vintage artifact more than worth preserving, and it’s great that Blue Underground included it here. It would be great to see more of this sort of thing on future releases rather than spending the money on newer, narrowly-focused interviews and commentary. First from the previous DVDs is an interview with Franco Nero and under-appreciated neo-realist Ruggero Deodato (who directed Cannibal Holocaust but served as the assistant director on Django). The two have plenty of very worthwhile anecdotes to share, from how Franco Nero got his screen name to why Deodato decided to give all his extras wear red masks during the film. It’s a wonderful, if all too brief, chat with two legends, and it ends fittingly with Nero talking about the possibility of getting back in the saddle as our favorite gunslinger.

First from the previous DVDs is an interview with Franco Nero and under-appreciated neo-realist Ruggero Deodato (who directed Cannibal Holocaust but served as the assistant director on Django). The two have plenty of very worthwhile anecdotes to share, from how Franco Nero got his screen name to why Deodato decided to give all his extras wear red masks during the film. It’s a wonderful, if all too brief, chat with two legends, and it ends fittingly with Nero talking about the possibility of getting back in the saddle as our favorite gunslinger. Next is a ten-minute short film featuring Franco Nero, The Last Pistolero. While initially a little deliberately arthouse, it finds its form near the end and offers a fine little deconstruction of the western hero. With Nero in the lead and totally silent throughout, it’s as if his Django, and every other western staple, is coming face to face with karma, knowing that successfully dodging thousands of bullets a movie and somehow surviving eventually catches up with you. Presented in black and white, it’s a good looking little piece, but the non-anamorphic letterbox encode leaves much to be desired.

Next is a ten-minute short film featuring Franco Nero, The Last Pistolero. While initially a little deliberately arthouse, it finds its form near the end and offers a fine little deconstruction of the western hero. With Nero in the lead and totally silent throughout, it’s as if his Django, and every other western staple, is coming face to face with karma, knowing that successfully dodging thousands of bullets a movie and somehow surviving eventually catches up with you. Presented in black and white, it’s a good looking little piece, but the non-anamorphic letterbox encode leaves much to be desired.Rounding off the disc are English and Italian trailers and a short introduction from Mr. Nero himself.

wrapping it up...

Django is one of the grand characters of the cinema, a man woven with complexity, and one who behind that large brimmed hat still conceals so much of that from the audience. Eastwood may get too much credit as the penultimate anti-hero, but for my money Franco Nero’s guns that title down. Stylishly simple but scripturally complex, Django is a film both viscerally violent and emotionally complex. It’s one of the spaghetti greats. Blue Underground has pulled off an amazingly sharp and restored transfer, even if their signature noise dirties up the frame. The audio offers DTS options for both the English and the preferred Italian track with Nero’s original voice. The extras, while not the flurry of bullets the film deserves, complement the feature and provide a nice bit of retrospective. Blue Underground has a stable of great Italian westerns…hopefully they’ll open the coffin and set the rest of this fine era of filmmaking free like they have here with Django. Djangooooooooooo!

Django is one of the grand characters of the cinema, a man woven with complexity, and one who behind that large brimmed hat still conceals so much of that from the audience. Eastwood may get too much credit as the penultimate anti-hero, but for my money Franco Nero’s guns that title down. Stylishly simple but scripturally complex, Django is a film both viscerally violent and emotionally complex. It’s one of the spaghetti greats. Blue Underground has pulled off an amazingly sharp and restored transfer, even if their signature noise dirties up the frame. The audio offers DTS options for both the English and the preferred Italian track with Nero’s original voice. The extras, while not the flurry of bullets the film deserves, complement the feature and provide a nice bit of retrospective. Blue Underground has a stable of great Italian westerns…hopefully they’ll open the coffin and set the rest of this fine era of filmmaking free like they have here with Django. Djangooooooooooo! | overall... Content: A Video: B+ Audio: C+ Extras: B Final Grade: B |